As a recovering Caribbean braces for hurricane season, new data tools promise smarter response

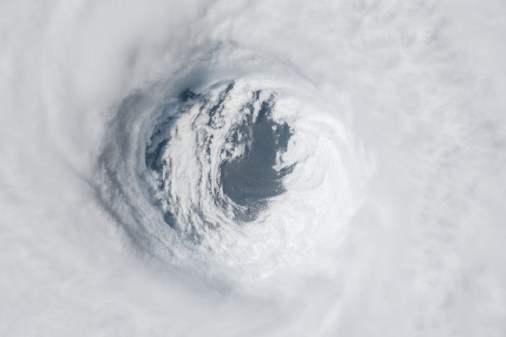

The 35-mph-winds and several inches of rain Tropical Storm Beryl brought to Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands last week were puny compared to the storms that battered them in 2017. But Beryl was still enough to show that the Caribbean’s infrastructure and residents are still recovering from the devastation wrought last year by Irma and Maria and that they may not be ready to weather the stronger storms expected to arrive later this summer.

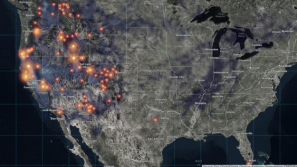

But new mapping and data tools being used to respond to storms in Louisiana and wildfires in California are providing emergency management new situational awareness capabilities, and those who have used the technology tell StateScoop it can help rally a smarter response to natural events like those expected to batter the islands later this year. As critical as those technologies could turn out to be, though, advanced data tools could be a hard sell for Caribbean territories that are still struggling to get foundational infrastructure back online.

While Beryl was downgraded from hurricane status before it reached the U.S. territories, it still managed to knock out power and water for thousands, cause several landslides and put a spotlight on the region’s tenuous situation with at least 10 more named storms expected this year.

Recent estimates in Puerto Rico place the number of FEMA-issued tarps still in use, which were intended to be temporary, at around 60,000. U.S. Virgin Islands Chief Information Officer Tony Riddick told StateScoop still about 40 percent of homes there can still be seen with tarps on their roofs.

“Most people can’t stand another Category 1 or Category 2,” Riddick said. “The slightest bit of wind will tear those things off and they’re back to square one.”

Last year’s hurricanes killed somewhere between 64 and 4,645 people in Puerto Rico alone, the higher-end estimates owing to medium- and long-term factors like the fallout from contaminated food and water sources or impeded access to healthcare. But a possible answer to mitigating those threats could lie in a new mapping and data tool being used now in Louisiana.

“It’s been a big deal, really ever since Katrina, having the ability to visualize something,” said Henry Yennie, a program manager who provides emergency support for critical healthcare facilities through Louisiana’s Department of Health and Hospitals.

Yennie said the addition of a mapping tool from geospatial data company Boundless has transformed how his agency responds to emergencies like hurricanes as they unfold. The software, he told StateScoop, compiles dynamic maps based on near-real-time bed status data provided by healthcare facilities and other data sources, allowing responders to quickly size up a problem and address urgent issues such as determining which hospitals with intensive-care patients are running on generator power.

Answering those kinds of questions could have better informed Louisiana’s response to Hurricane Gustav in 2008, when three major hospitals in Baton Rogue relying on generator power were not able to use their air conditioning, and temperatures inside rose into the 90s. It might’ve also prevented the drowning of 34 elderly and disabled patients who died in a nursing home in Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana, during Hurricane Katrina in 2005, after authorities decided it was unnecessary to evacuate.

With help from Boundless, Yennie said he can build a map and have a visual answer to a question in less than an hour.

“That capability to do those maps based on actual data is priceless. You can’t put a value to it,” Yennie said. “The bigger use case for them is facility status — in the run-up to a hurricane or ice storms people want to know how many hospitals are vulnerable, how many nursing homes are vulnerable.”

Using maps to be proactive in the face of an emergency is a universal challenge for first responders, Yennie said and estimated that improving adoption of data-based decision-making tools will be a cultural challenge for emergency management.

“At least in my experience,” he said, “there’s a lot of reacting to things.”

First responders elsewhere are looking to improve their awareness, but the technology isn’t always keeping pace with the demand for better intelligence. The Texas Department of State Health Services did some mapping of hospital statuses during Hurricane Harvey last year to track assets and also to plan mosquito spraying after the storm, a spokesperson told StateScoop, but getting those facility statuses was done “the old fashioned way: calling them.”

In the Virgin Islands, this type of technology could be purchased through relief funding provided by U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, which allocated $1.62 billion in block grants to the territory in April and an additional $243 million last week.

“One of the first things I’m going to ask for is predictive analysis tools to give us the visibility to shut things off, bring things offline, control things from a central location,” said Riddick. “That’s something I would have wanted to have when I first got here [in 2016].”

Getting software into the territory would be relatively light lift. After last year’s hurricanes, Riddick said he was approached by lots of vendors offering to help, but who weren’t aware of the challenges they would face in deploying what might be a straightforward operation in the states.

“When you’re talking about coming here, everything is down, everything is broken,” Riddick said. “You can’t get on the phone and say ‘Hey, drive a couple telephone poles over.'”