How skeptics called Big Telecom’s bluff on broadband coverage maps

The Federal Communications Commission will soon divvy up $4.53 billion to cellphone carriers as part of an initiative to expand high-speed internet access in rural, underserved areas all across the country, but before it does, there’s the matter of the maps.

When the FCC announced on Dec. 7 that it was investigating the coverage maps that carriers had provided, it put a spotlight on a quiet, nationwide process in which independent organizations and state and local officials had been checking whether the coverage was truly as pervasive as those companies had claimed.

Across the country, public and private stakeholders had collected data that brought scientific measurement to bear against claims by companies that ran counter to the intuition and the first-hand experience of many involved. Two of those investigators were Clay Purvis and Corey Chase, who work in the telecommunications and connectivity division of Vermont’s Department of Public Service. After the FCC had opened the challenge process in March, they spent months traversing their state to conduct their own speed tests to challenge the phone companies’ data.

The FCC’s rural broadband program, known as Mobility Fund Phase II, will distribute subsidies to carriers based on coverage maps supplied by those companies. To ensure the coverage data is accurate, companies are required to submit their map data under penalty of perjury.

More than 20 million speed tests challenging the maps were filed with the FCC. Across the 37 states that filed challenges, testers found what appear to be wide discrepancies between the provider-submitted maps and the independently collected data.

The maps, submitted by carriers like Verizon, AT&T, T-Mobile, Sprint and U.S. Cellular, as well as smaller, regional providers, “defy credibility,” Chase told StateScoop at his office in Montpelier.

The FCC investigation, which may have been triggered by a claim about the accuracy of Verizon’s coverage map, did not specify which carriers were under investigation. Verizon’s submitted coverage map, according to the Rural Wireless Association, “grossly overstates” the company’s actual broadband footprint. The RWA also filed a similar complaint to the FCC related to T-Mobile’s coverage map on December 10. The FCC declined comment, and Verizon and T-Mobile did not respond to request for comment.

In the Dec. 7 announcement, Chairman Ajit Pai emphasized the need for accuracy in ensuring that Americans have access to high-speed internet. “A preliminary review of speed test data submitted through the challenge process suggested significant violations of the Commission’s rules [by cell carriers],” Pai said.

For Chase and Purvis, the work was worth it, even if proving companies wrong wasn’t their initial goal.

“I think that the idea going into it was that there would be little discrepancies here and there, and if you knew of a place that didn’t have cell coverage, you could go out and challenge that place,” Purvis said. “But states called the companies’ bluff, and did widespread challenges. I think we poked enough holes in the data that it called into question the entire data set.”

‘Not believable’

Chase and Purvis only learned about the FCC’s challenge during a May webinar, so late that the FCC’s initial Aug. 27 deadline to contest its broadband coverage map seemed unfeasible, but they began putting together a potential plan anyway.

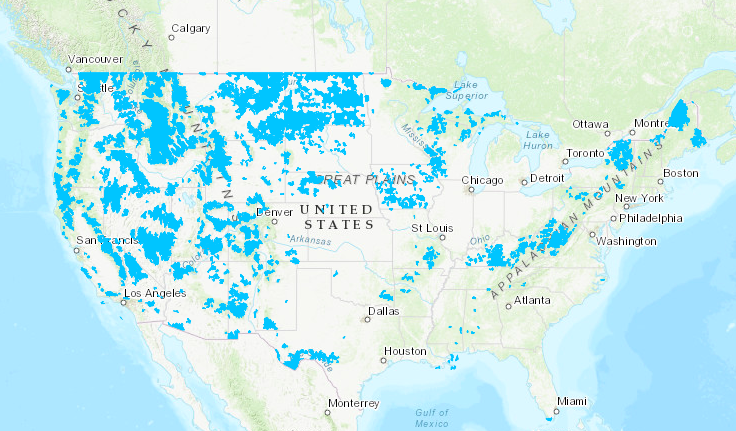

In February, the FCC had asked cellphone providers in the United States to submit maps of their coverage areas. The blue regions in the combined map, below, show the regions where no carrier claimed coverage. The map suggests that much of the eastern half of the United States enjoys 4G LTE coverage from at least one provider, as do sparsely populated states like Oklahoma and Kansas.

Mobility Fund II Initial Eligible Areas Map (FCC)

That level of coverage is “not believable,” Chase said, citing his own experience traveling to regions that don’t have any coverage at all.

Once the FCC built its national map aggregated from the information the carriers submitted, it divided each state into one-square-kilometer blocks. To contest the coverage of a block successfully, the challenger — a government entity, a lawmaker’s office or a nongovernmental organization — had to show that at least 75 percent of the area did not have 4G LTE coverage of at least five megabits per second, the speed required to reliably watch Netflix or make a video call on Apple FaceTime.

Challengers were required to conduct their speed tests on phones from a list of approved devices curated by the carriers themselves, which favored the newest and most expensive models. The Vermont team spent more than two thousand dollars on new phones for its tests; while West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin’s office, unable to acquire new equipment for its challenge, used staff members’ personal devices.

But efficiently testing broadband speeds through 75 percent of a one-square-kilometer block — not necessarily located on major roads — proved near-impossible, Chase said, because if a road did not cut through 75 percent of a block, hiking and speed testing with cell phones in hand became the only option. Even with the FCC extending its initial deadline by 90 days to Nov. 26, challenging every block was unrealistic. Manchin’s office only challenged three square kilometers, for example.

Vermont was broken up into about 25,000 blocks. After the deadline extension, Chase spent two months driving nearly 7,000 miles with a cardboard box of six phones in the passenger seat — one on each carrier serving the state — running speed tests every 20 seconds. Making the process even more daunting, the FCC’s official speed test app didn’t allow for tests to be conducted while moving.

The whole thing was “archaic,” Chase said.

Stopping every few feet to run a stationary test would have greatly prolonged the testing process, so Chase, Purvis and Hunter Thompson, the director of shared services for the Vermont Agency of Digital Services, found an app that could measure internet speed while the car was moving along Vermont’s roads. Thompson and Chase worked with the app’s Bulgarian developer, Julian Gyokov Binev, to create a new process in the app that filed all the data from each speed test into a single row in a spreadsheet, the FCC’s desired format.

Chase and Purvis’s tests resulted in challenges to the map in regions of Vermont where at least one carrier had claimed coverage, but where they didn’t find any. This included near Montpelier and the southern end of the state. The FCC’s ongoing investigation will determine how expansive these discrepancies may be.

But even if those challenges are verified, future service in unserved areas isn’t a guarantee. The $4.53 billion pot will be distributed through a reverse auction, but cell carriers are not required to bid on the areas found not to have service. If that happens, said FCC spokesman Mark Wigfield, he’s not sure what will happen next.

‘Hitting pause’

In order to understand the challenge process, Chase said, it’s important to understand that the FCC is counting on the providers’ maps to be correct. If they aren’t, the providers could be guilty of perjury — which, he said, sets an extremely high burden of proof for any party challenging the maps’ accuracy. “The bar for you to reach, to claim that the data is wrong, is so high as to make it almost impossible,” Chase said.

In his announcement earlier this month, Pai, a former Verizon lobbyist, insisted that accurate data from providers is what’s necessary to proceed with the auction process.

“My top priority is bridging the digital divide and ensuring that Americans have access to digital opportunity regardless of where they live, and the FCC’s Mobility Fund Phase II program can play a key role in extending high-speed Internet access to rural areas across America,” Pai said in a press statement. “In order to reach those areas, it’s critical that we know where access is and where it is not. That’s why I’ve ordered an investigation into these matters. We must ensure that the data is accurate before we can proceed.”

The process is now on hold before a response period in which carriers can submit new coverage maps after reviewing the challenged locations. The FCC hasn’t stated how long its investigation will take, though, and the pause has raised concerns for Manchin, who has said he will hold up the re-appointment of FCC Commissioner Brendan Carr until the agency clarifies what steps it will take following its investigation into the carrier maps.

“After years of sounding the alarm about the inaccurate mapping and proving it wrong with his own testing, Senator Manchin is happy to see the FCC finally addressing the inaccuracies,” Manchin press secretary Sam Runyon told StateScoop in an email. “However, he is concerned that the FCC has not indicated how long this investigation will take. The mapping problem is much bigger than the Mobility Fund so putting an indefinite hold on reallocating existing mobile broadband subsidies is not the best way to solve it.”

But it appears that the efforts made by Chase, Purvis and other challengers have paid off, at least to the point of triggering further examination of providers’ maps.

“I’m glad that the FCC is taking this action,” Purvis said. “I think it’s a positive step. What I would like to see come out of this investigation is a corrected map and a path for carriers to take that money and serve our unserved areas. We just want cell coverage.”