Election systems safe from cyberattacks, experts believe

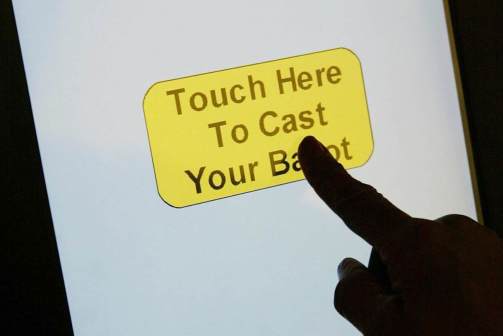

With the 2016 national election looming, experts testifying Tuesday before a House committee broadly expressed confidence that election systems are secure from cyber and other disruptive attacks — with a few cautionary notes.

“I know of no jurisdiction where voting machines are connected to the Internet,” David Becker, executive director of the Center for Election Innovation and Research, told members of the House Committee on Science, Space and Technology. “This makes it nearly impossible for a remote hacker, whether in Moscow, Idaho, or Moscow, Russia, to access the equipment and plant malicious code or otherwise hack the system.”

The complexity of the election system — there are about 10,000 jurisdictions that administer the voting process individually — is another factor.

“There isn’t a single or concentrated point of entry for a hacker,” Becker said. “Rather there are thousands of points a hacker would have to successfully navigate to manipulate the results of a national election.”

However, Dan Wallach, a professor of computer science at Rice University in Houston, was more circumspect. “Being disconnected from the Internet helps, but it’s not a panacea,” he said. Paperless electronic voting systems, “despite not generally being connected to the internet…were never engineered with security in mind. Our nation-state adversaries have the capability to execute attacks against these systems.”

Wallach told the committee that Russia was behind a cyberattack on Ukraine’s 2014 election, “where a hacked tabulation system would have reported results favorable to Russia. Ukrainians were lucky enough to catch this.” He offered no further details about that attack.

“We must prepare for the possibility that Russia or other sophisticated adversaries will use their cyber skills to attack our elections, and they need not attack every county and every state,” Wallach said. “It’s sufficient for them to go after battleground states, where a small nudge can have a large impact. The decentralization is helpful but not sufficient.”

Wallach told the committee that his top concern was about cyberattacks on online voter registration systems, which are connected to the internet, citing recent attempts to hack registration rolls in Arizona and Illinois.

Tom Schedler, secretary of state for Louisiana, told the committee the attacks in Arizona and Illinois were “a sobering wakeup call on the serious nature of cyberattacks.”

But he added that such attacks wouldn’t prevent elections from proceeding. “While it would certainly be disruptive to have registration systems hacked, as we saw in Arizona and Illinois, voters could still vote and election day would still occur,” he said. “No voter information was added or deleted in Arizona or Illinois.”

Becker speculated that the Arizona and Illinois attacks were aimed at “accessing personal data for purposes of identity theft, not to manipulate voter lists.”

Wallach, however, said a successful attempt to damage or destroy a voter registration database could “disenfranchise a significant number of voters, leading to long lines and other difficulties.” Additionally, the Arizona and Illinois attacks are only the ones we know about. “There might be more,” he said.

Wallach is also concerned about vote tabulation systems. “Generally speaking, these tend to be old computers running old operating systems, in some cases [Microsoft] Windows 2000, where security patches aren’t even available from the vendor anymore,” Wallach said. “That means there are significant vulnerabilities.”

Rep. Zoe Lofgren, D-Calif., pointing to a suspected Russian cyberattack this year on the Democratic National Committee’s computer network, agreed large-scale attacks on voting precincts and on vote tabulation systems are “unlikely to succeed.” But she worried that attackers could disrupt an election simply by creating chaos.

“That is the goal of the attack on the Democratic Party and it also may be goal of the cyber attack on the [Arizona and Illinois] systems,” she said.

Lofgren suggested that bad actors who hack data from voter registration rolls could send emails to voters informing them that the date of the election had been changed or their precinct had been changed.

“Wouldn’t that create chaos in a system, if even a small percentage of those voters believed an email misadvising them? The goal is not necessarily to impact the tabulation but to create long lines of people, to create chaos, to attack the faith and confidence that the American people have in their election system,” she said. “It’s very chilling to think what could happen this November.”

But Becker insisted that disrupting an election on national scale would be nearly impossible. “No system is 100 percent hack-proof, but elections in this country are secure, perhaps as secure as they have ever been,” he said.

“To manipulate election results on a state or national scale would require a conspiracy of literally hundreds of thousands and for that massive conspiracy to go undetected,” he said. “Even if it could, it would likely have no effect on the vast majority of election results nationwide because over 75 percent of voters vote on paper ballots or on a device that creates a paper record.”

Still, Wallach said, jurisdictions should be prepared. “It’s important to make plans now for recovering from unforeseen cyber disasters,” he said. “Our election systems face credible cyber threats from our nation-state adversaries and it is prudent to adopt contingency plans before November to mitigate these threats.”