Voter registration ‘a huge target’ for ransomware

State and local election officials manage their voter registration databases using several pieces of software known to be favorite targets of ransomware actors, a leading ransomware analyst said during a webinar Thursday.

Allan Liska, of the cybersecurity firm Recorded Future, said that many voter files are hosted on Microsoft SQL Server or Oracle database software, with many end-user devices still running on operating systems that are no longer supported by their manufacturers, like Windows 7. And state and local agencies’ reliance on third-party vendors for system updates often means their networks are accessed remotely using software like Microsoft Remote Desktop Protocol or Citrix, both of which have been found to be vulnerable to ransomware threats.

“Citrix has become a very prominent attack point for ransomware actors,” he said.

While ransomware has long troubled state and local governments at large, it has become a more acute fear for election administrators in the run-up to this year’s presidential election. Last month, a federal cybersecurity consultant warned county leaders that a ransomware attack could lock officials out of their voter registration databases or encrypt the websites where unofficial results are posted. In February, the Department of Homeland Security’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency included a ransomware scenario in a “tabletop in a box” kit it distributed to state and local election officials.

Liska sounded a similar note in his presentation Thursday, and warned attendees that a ransomware attack on an election system could also include the extortion tactics that many hackers, such as those behind the Maze malware, have popularized.

He walked through what might happen if a ransomware actor gained access to a government network containing a voter list. While a ransomware attack might not stop an election from being conducted — especially if the victim has offline backups of its voter registration file — it could still embarrass a state or municipality, he said.

“They’ve probably stolen some of that voter registration data and they now threaten to post that data to the extortion site,” Liska said.

He went on to say that stolen data could either be published for everyone to see or sold to other opportunistic hackers on a dark-web marketplace.

“Or if we’re being honest, because ransomware actors are bastards, both,” he said.

There are a few defensive measures state and local officials can take, though, including regularly backing up voter registration files to offline storage or paper. Many states, like Pennsylvania, back up their registration databases daily. States also take a variety of approaches to voter registries. While most take a top-down approach, in which the database is kept at the statewide level, with data being pushed out to local counties, a handful use a bottom-up system, in which counties collect the official voter files and funnel data up to the state. Others use a hybrid of the two practices.

The bottom-up approach is harder to target with a coordinated ransomware attack, Liska said. But, he added, ransomware does not need to be a coordinated effort. While there are only about a dozen active forms of ransomware, they are sold like software as a service.

That, along with a resurgence in attacks following a brief dip at the start of the coronavirus pandemic, means election administrators need to be vigilant over the next three months, he said.

“Even with the slowdown because of the COVID-19 pandemic, we’re going to see more attacks,” he said. “Ransomware actors have grown more sophisticated, especially with the advent of big game hunting. Ransomware actors know voter databases are a huge target.”

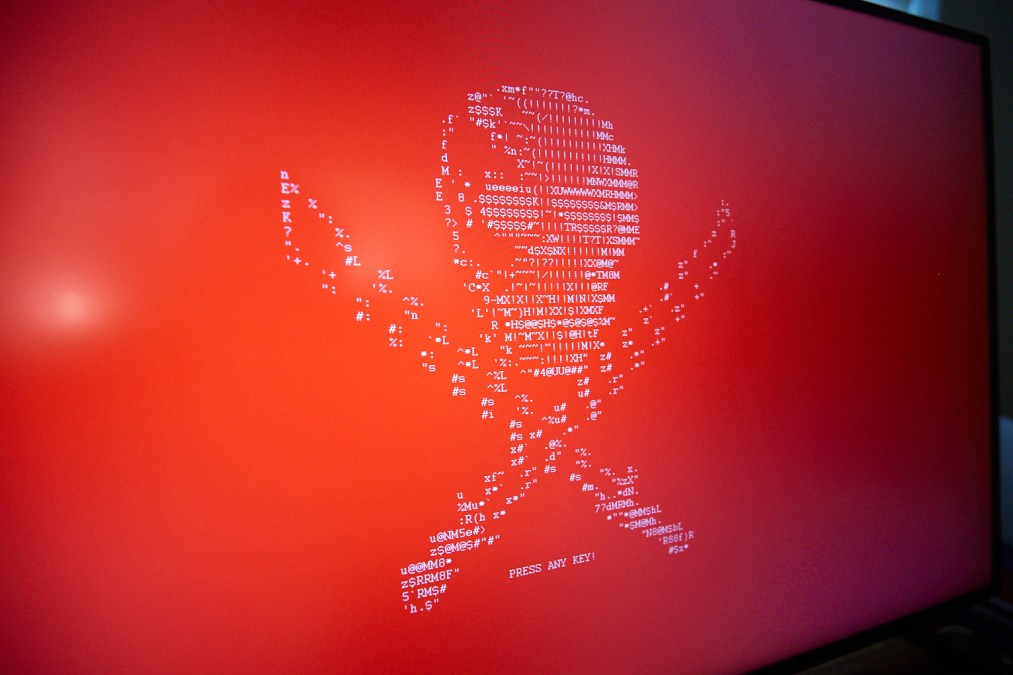

[ransomeware_map]