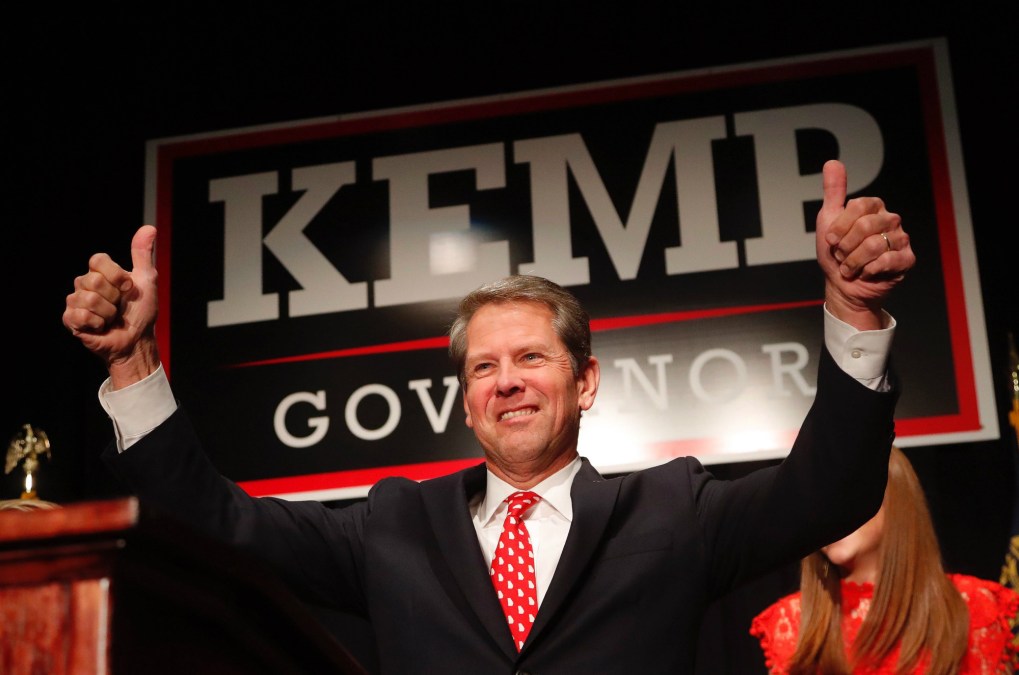

Georgia has not followed good election security practices, cyber expert says

Georgia Secretary of State Brian Kemp’s Nov. 3 accusation that Democrats attempted to hack the state’s voter registration database three days before a gubernatorial election he would go on to win was blasted at the time by cybersecurity experts, who said Kemp offered little evidence to support his claim. Six weeks later, a report confirming that Kemp made his accusation based on a single piece of flimsy evidence, and that no law-enforcement investigations ever took place, strongly suggests Georgia has ignored good election security practices, an expert in the field told StateScoop.

Eric Hodge, the director of election security services for the security firm CyberScout, responded to a Dec. 14 report by the Atlanta Journal-Constitution that found that Kemp’s claim that Democrats tried to hack the state voter file was based on a lone email to a Democratic volunteer from a software developer who said he found vulnerabilities in the database. In his capacity as secretary of state, Kemp, who resigned Nov. 8, was Georgia’s top elections official, leading to criticisms about whether he should oversee an election for governor in which he was also the Republican candidate.

Kemp defeated Democrat Stacey Abrams by about 55,000 votes, a margin that the Journal-Constitution reported could’ve been swayed by his last-minute accusation of an attempted cyberattack.

“In this case, it seems the Georgia leadership shot the messenger and thought the messenger was representing a political opponent and accused them of malfeasance,” Hodge said. “It had the feel of a political reaction.”

The vulnerabilities in question were spotted when the developer, identified by the Journal-Constitution as Richard Wright, logged on to Georgia’s voter website to check his registration. Upon attempting to download a sample ballot, Wright discovered the site allowed public users to download any file, and that altering certain numerals in the URL for a voter registration allowed users to access any Georgia voter’s file, containing many lines of personally identifying information. Wright eventually emailed his concerns to the state Democratic Party, which forwarded it to security experts at Georgia Tech.

A Washington, D.C., lawyer, whom Wright had also contacted, relayed his findings to the FBI, as well as lawyers representing Georgia in a lawsuit over the state’s use of touchscreen voting machines, the Journal-Constitution reported.

Rather than thank concerned citizens for spotting a potentially critical security flaw, though, Kemp’s office turned the discovery into a political weapon.

“I can tell you most companies around the world and state governments I’ve worked with would welcome news about vulnerabilities so they could fix them,” Hodge said.

But Kemp’s turning an alert about website vulnerabilities into a political cudgel wasn’t the first time Georgia has strayed from good cybersecurity practices, Hodge continued. He also cited the July 2017 decision by the Center for Elections Systems at Kennesaw State University, which ran Georgia’s voting-related computer systems until this year, to wipe a server that had been configured in way that exposed 6.5 million voter registration records during the 2016 election. That was the same year Kemp rejected federal assistance to conduct intrusion scans of his voter database.

The server’s configuration, researchers said later, left voter records susceptible to alterations from unauthorized users.

“All those activities and the continuation of a critical vulnerability would indicate a lot of this was not taken care of,” Hodge told StateScoop.

He also said that voter database vulnerabilities like those found in Georgia offer reminders that even if the voting machines aren’t physically hooked up to any networks, they still potentially contain vulnerabilities.

“Two years ago, there wasn’t as much concern about whether the hacking thing was real,” Hodge said. “The mantra was that our voting machines are not connected to the internet, so votes can’t be changed. That mentality has changed steadily. Georgia’s machines are not connected to the internet, but I can connect to Kennesaw State and access the voter database.”

If there’s a silver lining in Georgia’s latest fracas over its statewide voter file, it’s that Kemp’s ascension to the governor’s mansion means a new secretary of state in Brad Raffensperger, a Republican state legislator who has said he wants to increase the office’s cybersecurity measures.

“I’m glad he’s not secretary of state anymore,” Hodge said of Kemp, who also once mistook a federal employee’s renewal of a professional license issued by his office for a cyberattack perpetrated by the Department of Homeland Security. “As governor, he probably won’t focus so much on cybersecurity.”